掃一掃關注公眾號

資訊中心

- 企業動態

- 行業資訊

-

-

-

202404-29

喜訊!眾興菌業榮獲“2024年甘肅省五一勞動獎狀”...

4月25日,2024年甘肅省慶祝“五一”國際勞動節暨表彰省五一勞動獎大會在蘭州召開,省委副書記石謀軍出席并講話。會議表彰......

-

202111-02

眾志成城 齊心抗疫

眾志成城齊心抗疫天水眾興菌業創始人陶軍先生通過天水眾興愛心慈善基金會以個人名義捐款100萬元助力天水市疫情防控 11月2......

-

202110-29

眾志成城齊心抗疫 眾興有愛共克時艱 | 天水眾興...

此次疫情爆發以來,天水社會各界眾志成城、攜手抗疫,筑起了一道抗擊疫情的長城。在積極響應市委、市政府號召,切實做好自身防護......

-

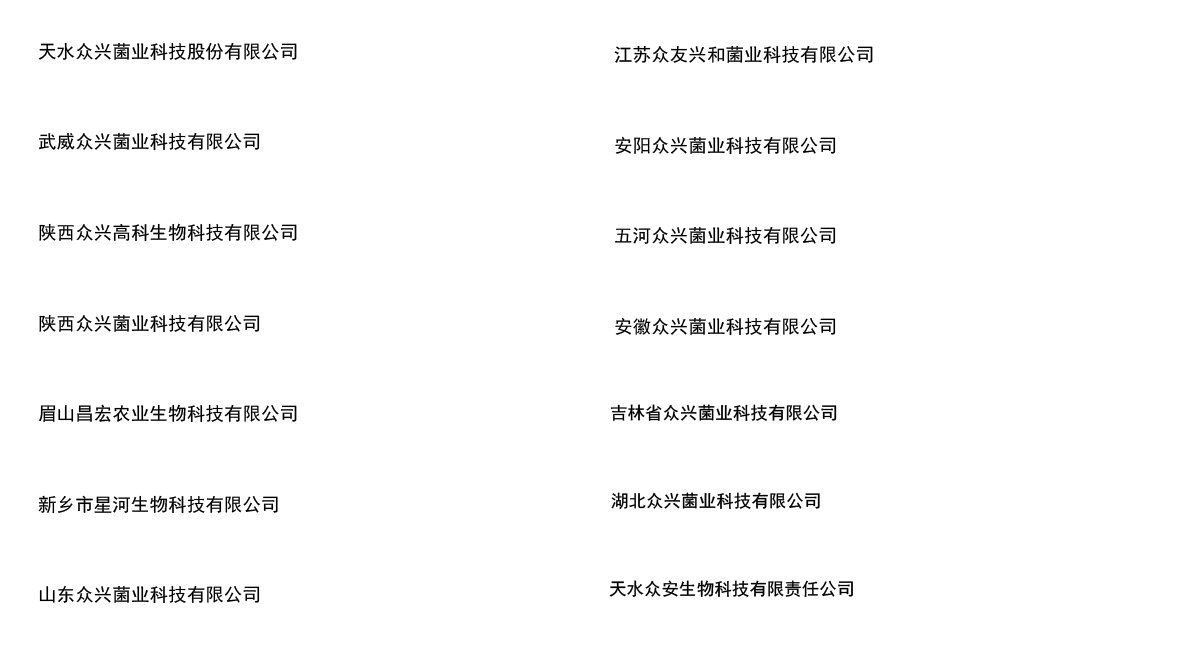

眾興菌業子公司、參股公司

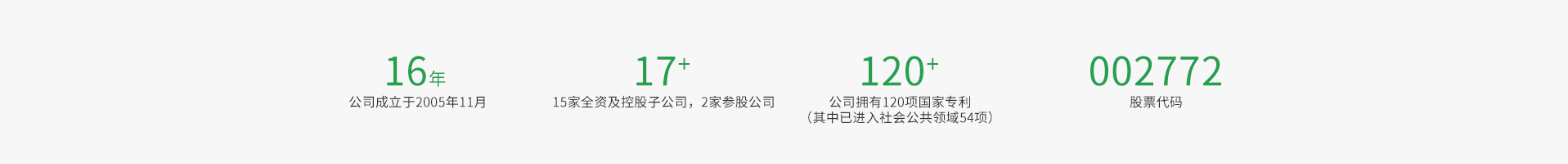

關于眾興

隴ICP備15000774號-1 天水眾興菌業科技股份有限公司

甘公網安備 62050302000151號